The 'Cringe' Replay Loop: Why Your Brain Won't Let It Go

It’s 2 AM. The house is quiet, the blue light from your phone casting long shadows on the ceiling. And then it hits you—a memory from seven years ago. The time you tripped on stage, mispronounced a word in a big meeting, or told a joke that landed with a deafening thud. Your cheeks flush hot, your stomach plummets, and your whole body tenses as if it's happening all over again.

As your emotional anchor, Buddy is here to wrap you in a warm blanket and tell you: that feeling is real, it’s intense, and you are not broken for having it. This isn't just you being 'dramatic.' It's a primal, biological response. Your brain is wired for social connection, and it registers social blunders as genuine threats. That replay loop is a misguided attempt by your mind's security system to ensure you never make that 'dangerous' mistake again.

The constant rumination and anxiety you feel are symptoms of a system trying to protect you, not punish you. The problem is, the system is outdated. It doesn't know the difference between being chased by a predator and being momentarily awkward at a party. The key to learning how to get over an embarrassing moment isn't to fight this feeling, but to understand it with kindness and gently guide your brain back to safety.

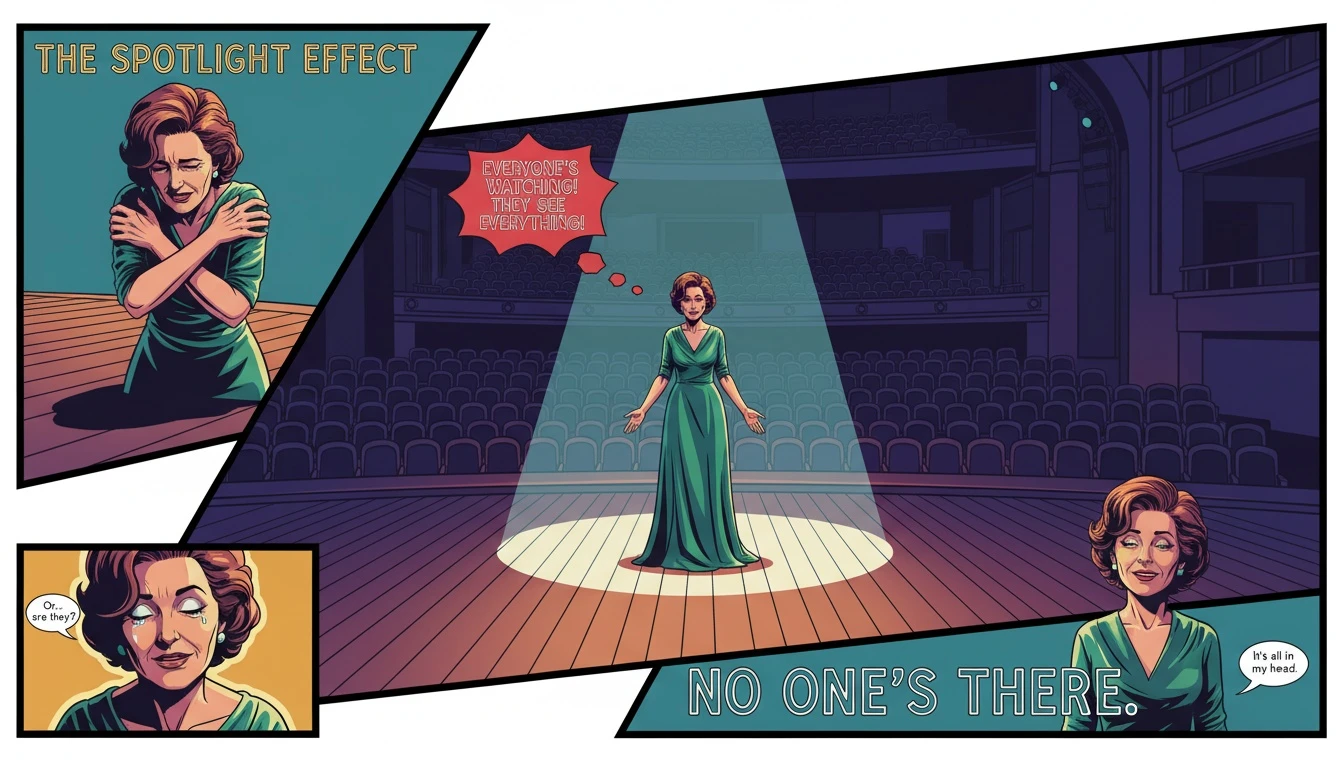

The Spotlight Effect: The Truth Is, Nobody Cares as Much as You Do

Alright, let's get our reality surgeon, Vix, in here for a dose of freeing truth. You're replaying that moment on a loop, convinced it’s seared into the memory of everyone who witnessed it. You believe there's a permanent file in their brains labeled 'That Time You Were Super Cringe.'

Here’s the fact sheet: That file doesn't exist. They've forgotten. They were thinking about their own deadlines, their weird haircut, or what they were going to eat for lunch. This isn't just an opinion; it’s a well-documented psychological phenomenon.

It’s called the spotlight effect psychology, a cognitive bias where we vastly overestimate how much other people notice our appearance or behavior. As research points out, we feel as though we are walking around with a giant spotlight on our heads, illuminating our every flaw. The truth? Everyone is too busy starring in their own movie to pay that much attention to a supporting character in yours.

Your most humiliating memory is, at best, a forgotten bit of background noise in someone else’s day. It feels massive to you because it's your story. To them, it wasn't even a scene. Letting go of the cringe requires accepting this blunt, beautiful fact. The first step in figuring out how to get over an embarrassing moment is realizing you're the only one still holding onto it.

Your 3-Step 'Cringe' Recovery Plan: Reframe, Reassure, Release

Now that we’ve established the emotional reality and the factual reality, it's time to bring in our strategist, Pavo, for an actionable game plan. You can't just wish the feeling away; you need a process. This is the move to stop replaying embarrassing moments in your head and start building resilience.

Step 1: Reframe the Narrative

Right now, the memory is framed as a horror story starring you as the villain or the fool. Your job is to become the editor. Reframe it as a comedy, a learning experience, or simply a neutral data point. The goal isn't to erase the memory but to strip it of its power. A practical method for how to get over an embarrassing moment is to write it down as a funny, third-person story. This creates distance and shifts your perspective from participant to observer.

Step 2: Reassure with Self-Compassion

The internal critic that replays the cringe moment is loud and cruel. You must counter it with a voice of deliberate kindness. This isn't about letting yourself off the hook; it's about practicing self-compassion for past mistakes. When the memory surfaces, don't say 'I'm so stupid.' Use this script: 'That was an awkward moment, and it’s okay that I feel embarrassed. I was doing my best then, and I've learned from it.' Forgiving yourself for being awkward is a radical act of self-preservation.

Step 3: Release the Energy

Finally, make a conscious decision to release the emotional charge. Rumination keeps the memory stuck in your body. Get it out. Talk about it with a trusted friend, journal about it until there's nothing left to say, or do something physical. Go for a run, dance in your kitchen, or scream into a pillow. The physical act signifies to your brain that the 'threat' is over and the loop can be closed. This is how to get over an embarrassing moment for good—by completing the emotional cycle and letting go of the cringe.

FAQ

1. Why do embarrassing moments feel so physically painful?

Embarrassment triggers a mild version of the fight-or-flight response, a social survival instinct. Your brain perceives the social blunder as a threat to your standing in the group, releasing stress hormones like adrenaline that can cause a racing heart, hot cheeks (blushing), and a sinking feeling in your stomach.

2. How can I stop ruminating on past mistakes at night?

To stop the replay loop, try externalizing your thoughts before bed. Spend 10 minutes journaling everything that's on your mind. This 'brain dump' can clear your head. Alternatively, practice a simple mindfulness exercise, focusing on your breath to gently pull your attention away from anxious thoughts about the past.

3. What's the difference between embarrassment and shame?

Embarrassment is typically a fleeting, public feeling about a specific action ('I did a clumsy thing'). Shame is a much deeper, more painful feeling that attacks your identity ('I am a clumsy person'). Learning how to get over an embarrassing moment often involves preventing it from turning into lasting shame through self-compassion.

4. Is the spotlight effect a real psychological concept?

Yes, the spotlight effect is a well-documented cognitive bias. Studies show that people consistently overestimate how much others notice their actions and appearance. Understanding this concept is a powerful tool because it provides logical proof that your embarrassing moment was likely not as significant to others as it was to you.

References

psychologytoday.com — The Unimportance of Embarrassment