The Silence Before the Roar

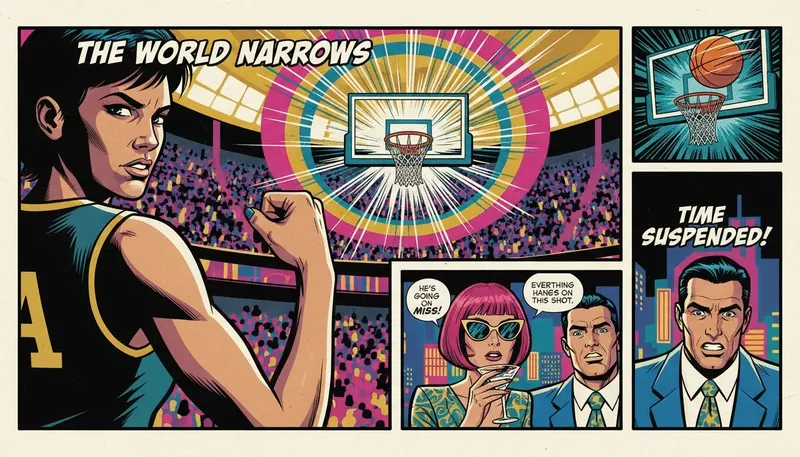

The entire stadium holds its breath. It’s a sound you can feel—a vacuum of noise that pulls at your skin. Your heart is a drum against your ribs, a frantic rhythm only you can hear. Sweat slicks your palms, not from heat, but from the crushing weight of the moment. This is the final play, the championship point, the last shot.

In this crucible, legends are forged and hearts are broken. One person steps up, their movements fluid and automatic, as if the pressure is a different form of oxygen. Another, equally skilled and trained, suddenly finds their limbs are made of lead. Their mind, usually a supercomputer of strategy, is now filled with static. They choke.

We’ve all seen it. We’ve all wondered what separates the two. It feels like magic, like some are just born for the spotlight. But the truth is far more scientific and, encouragingly, far more controllable. Understanding what makes an athlete clutch isn't about mythology; it's about deconstructing the psychology of performance when everything is on the line.

The Fear of the Final Play: Why Some Athletes Choke

Let’s start by wrapping our arms around that feeling of panic. That sudden thought of 'don't mess this up' that seems to paralyze you. That’s not a character flaw. It's your brain's ancient, powerful protection system going into overdrive. Your desire to succeed is so immense that your body interprets the stakes as a genuine threat.

When this happens, your prefrontal cortex—the part of your brain responsible for rational thought and decision-making—can get hijacked. As explained in research on the psychology of performance, pressure causes you to start thinking too much about actions that should be automatic. You begin monitoring every detail of your swing, your shot, your stride, which disrupts the fluid, practiced motor skills stored in other parts of the brain. This is the very definition of the psychology of choking vs clutch performance.

This phenomenon is often explained by the Yerkes-Dodson law in sports, which suggests that our performance improves with mental and physiological arousal, but only to a certain point. A little bit of nervous energy makes you sharp. Too much, and your arousal levels and athletic performance plummet. It’s a delicate balance.

So, if you’ve ever felt that freeze, know this: It wasn't stupidity or a lack of talent. It was your brave desire to win becoming so overwhelming it momentarily short-circuited the system. The key to what makes an athlete clutch is learning to regulate that powerful emotional energy.

Inside the 'Quiet Eye': The Neurological Trick of Clutch Performers

Let’s reframe the problem. Choking isn't a moral failure; it's a data-processing error. The clutch performer, then, is simply a more efficient data processor. This is where we see the key mental characteristics of elite athletes emerge not as personality traits, but as trainable neurological habits.

One of the most significant discoveries in this field is the 'quiet eye' technique. Studies show that just before executing a critical motor task, elite performers have a longer and steadier gaze on their target than their less-successful counterparts. A basketball player will hold their gaze on the rim for a fraction of a second longer; a golfer will fixate on the ball without darting their eyes around.

This isn't just about looking. This prolonged, steady focus actively calms the parts of the brain that want to panic and over-analyze. It signals to your nervous system that it's time to execute a program that has been run thousands of times in practice. It’s the neurological key that unlocks a flow state in sports, allowing the body to perform with unconscious competence.

The mystery of what makes an athlete clutch is often solved by looking at where their eyes are. They aren't thinking about their elbow or their grip; they are absorbed by the target. They've learned to externally focus, which quiets the internal noise. And here's the permission slip: You have permission to stop actively 'trying' in the final moment. Your training did the work; your only job now is to focus your gaze and let your body do what it already knows how to do.

Train for the Moment: How to Simulate Pressure in Practice

Theory is liberating. Strategy is power. We understand the 'why,' so now let's build the 'how.' You don't hope for clutch moments; you engineer the resilience for them in practice. Learning how to perform well under pressure is a systematic process.

Here is the move. To master pressure in competition, you must first introduce it in training. Your goal is to make the stress of practice so similar to the stress of a game that your brain no longer registers a major difference. This is central to building the skill of what makes an athlete clutch.

Here is your action plan:

Step 1: Introduce Scrutiny and Consequence. Don't just shoot free throws. Shoot free throws where the rest of the team has to run sprints if you miss. Have a coach or teammate stand over you, critiquing your form aloud. This simulates the feeling of being watched and the weight of your actions affecting others.

Step 2: Train with Intentional Distractions. The game isn't silent, so your practice shouldn't be. Play recordings of loud crowd noise. Have teammates wave towels or talk while you're trying to concentrate. This trains your brain's filtering mechanism, making it easier to lock in and find that 'quiet eye' when it matters.

* Step 3: Drill Under Physical and Mental Fatigue. The biggest moments often happen at the end of a game when you're exhausted. Run sprints and then immediately execute fine motor skills like shooting, putting, or passing. This teaches your body to rely on its automated programming, not conscious effort, which is the secret to what makes an athlete clutch.

FAQ

1. Is being 'clutch' an innate talent you're born with?

While some individuals may have a natural predisposition to handle pressure, clutch performance is largely a trainable skill. Techniques like the 'quiet eye' and pressure simulation in practice can significantly improve an athlete's ability to perform in high-stakes moments, which is what makes an athlete clutch.

2. What is the Yerkes-Dodson Law and how does it relate to athletic performance?

The Yerkes-Dodson law is a psychological principle stating that performance increases with physiological or mental arousal, but only up to a point. When arousal levels become too high, performance decreases. For athletes, this means finding the optimal level of 'hyped up' without tipping over into anxiety that causes choking.

3. Can non-athletes use these techniques to perform better under pressure?

Absolutely. The principles of managing arousal, quieting the conscious mind to avoid overthinking, and focusing intently on the task at hand are applicable to public speaking, taking exams, job interviews, or any high-pressure situation. The core of what makes an athlete clutch is mental regulation.

4. What's the difference between being in a 'flow state' and being 'clutch'?

They are closely related. A 'flow state' is a state of complete immersion in an activity, where action feels effortless and time seems to distort. Being 'clutch' is often the result of achieving a flow state during a moment of intense pressure. The clutch performer accesses that state when it matters most.

References

psychologytoday.com — Choke: The Secret to Performing Under Pressure