The Fear of 'What If': Processing the Need to Find Answers

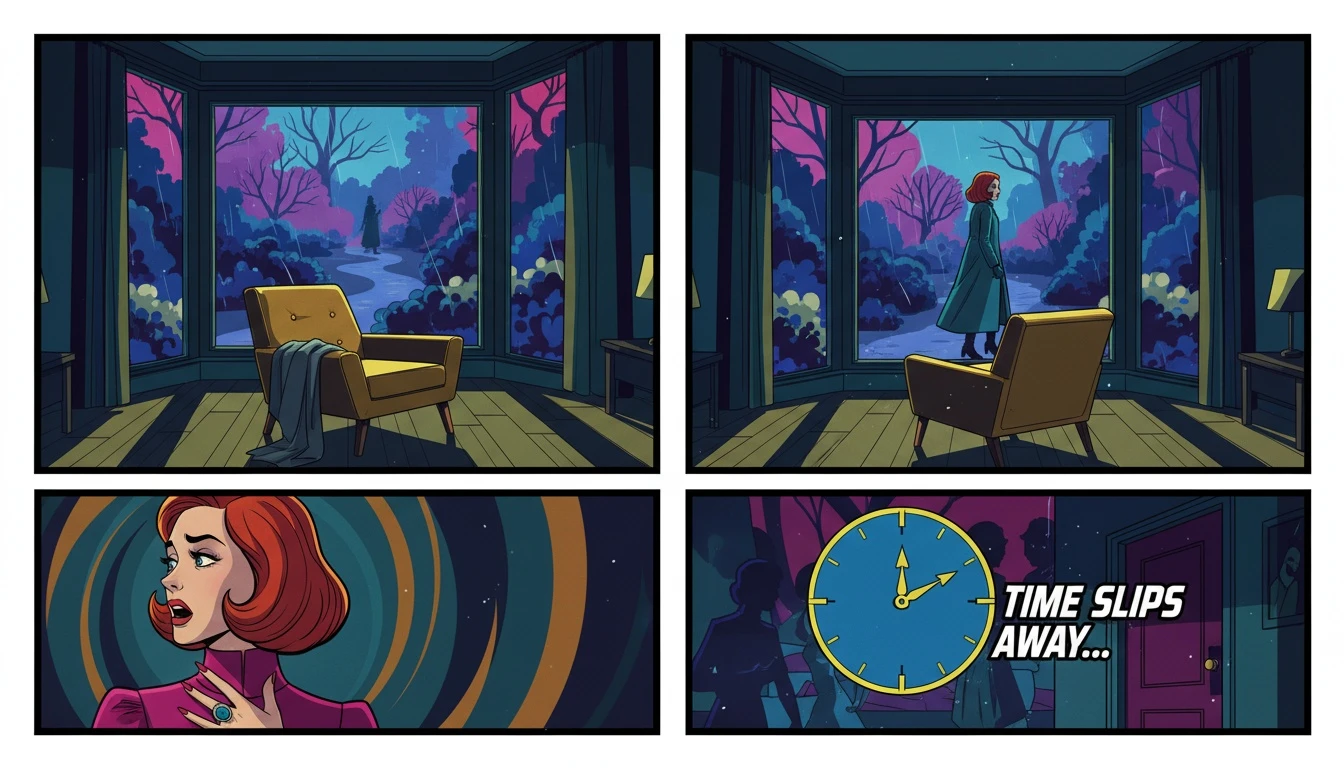

It’s a heavy weight to carry—the quiet, haunting rewind of memory. After a tragedy, the mind frantically searches for the breadcrumbs, the missed clues, the one moment where a different turn could have changed everything. You replay conversations, scrutinize old photos, and ask yourself, 'How did I not see it?'

Let's take a deep, collective breath right here. That feeling isn't about blame; it's about a profound and deeply human need to make sense of the unimaginable. Your search for the warning signs of psychosis in adults isn't morbid curiosity. It’s a testament to your compassion, a desire to protect the people you love and to find a map in a territory that feels terrifyingly uncharted.

When we look back, seemingly small things, like a pattern of `social withdrawal and isolation` or uncharacteristic irritability, suddenly feel like glaring red flags. This urge to find answers is a protective instinct. As our emotional anchor Buddy reminds us, 'That wasn't a failure to notice; that was your heart trying to protect itself and others. Your instinct to learn now is an act of love.'

Beyond Stereotypes: Recognizing Early and Active Symptoms

To move from anxiety to understanding, we need clarity. Our sense-maker Cory encourages us to look at the underlying patterns, not with fear, but with calm observation. Psychosis rarely appears overnight. It’s often preceded by a 'prodromal' period, where the early signs are subtle and easily mistaken for a bad mood or stress.

According to mental health experts at CAMH, these early `signs of schizophrenia in young adults` and other psychotic disorders can be gradual. They represent a noticeable shift from a person's previous level of functioning.

Early Warning Signs (The Prodromal Phase):

Changes in Emotion and Motivation: A new apathy or emotional flatness, a lack of motivation, or a general sense of unease and suspicion towards others.

Shifts in Thinking and Perception: Trouble concentrating, organizing thoughts, or a feeling that things are somehow 'different' or unreal. This is often where the first subtle warning signs of psychosis in adults begin.

Behavioral Changes: A marked `decline in personal hygiene` or grooming, abandoning hobbies, and a clear pattern of `social withdrawal and isolation` from friends and family.

Active Symptoms (The Acute Phase):

This is when the symptoms become more pronounced and unmistakable. These require immediate attention and professional `early psychosis intervention`.

Hallucinations: Hearing, seeing, or feeling things that are not there.

Delusions: Holding strong, fixed beliefs that are not based in reality, often accompanied by paranoia.

Disorganized Thinking: This can manifest as `disorganized speech patterns`, where a person jumps between unrelated topics or is impossible to follow.

Cory offers a crucial piece of validation here: *"You have permission to trust your intuition when you feel something is fundamentally 'off,' even if you can't name it yet. Your concern is data."

A Roadmap for Intervention: What to Do When You See the Signs

Recognizing the signs is the first step. The next is knowing how to act. Our strategist, Pavo, emphasizes that a clear plan can restore a sense of agency in a chaotic situation. If you're seeing the warning signs of psychosis in adults, here is the move.

Step 1: Document, Don't Diagnose.

Keep a private, factual log of the behaviors that concern you. Note dates, specific events, and direct quotes. This isn't for accusation; it's objective data that will be invaluable when you speak to a healthcare professional. Avoid labels like 'crazy' and stick to observations like, 'Stayed in their room for three days' or 'Spoke about ideas that felt disconnected from reality.'

Step 2: Initiate a Calm, Private Conversation.

Choose a time when you are both calm. Approach them with concern, not confrontation. Pavo provides a script:

'I've noticed [mention a specific, gentle observation, like 'you seem more distant lately' or 'that you haven't been sleeping well'], and I'm really concerned because I care about you. How have things been feeling for you?'

Focus on your feelings ('I am worried') rather than theirs ('You are acting strange').

Step 3: Seek Professional Guidance.

This is not something to handle alone. Contacting a primary care physician, a local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), or an `early psychosis intervention` program is critical. They can guide you on the next steps and provide resources for `what to do when someone is psychotic`.

Step 4: Collaborate on a Crisis Prevention Plan.

If the person is willing, developing a `crisis prevention plan` together can be empowering. This document outlines trusted contacts, preferred hospitals, medication information, and strategies to de-escalate a situation. It's a proactive tool that provides a clear roadmap during a potential emergency, ensuring your loved one's wishes are respected as much as possible.

FAQ

1. Can psychosis develop suddenly in adults?

While it can seem sudden, psychosis often has a gradual onset period known as the 'prodrome,' where subtle changes in behavior, thinking, and emotion occur. An acute psychotic episode might appear suddenly, but there were likely earlier, more subtle warning signs of psychosis in adults.

2. What's the difference between a bad mood and early psychosis?

The key difference is the severity, duration, and departure from the person's normal self. A bad mood is temporary and situational. Early psychosis involves a more persistent and significant decline in functioning, including social withdrawal, disorganized thoughts, and a growing disconnect from reality that is not typical for that individual.

3. How do you help someone who is in denial about their psychotic symptoms?

This is very common, a symptom called anosognosia (a lack of insight into one's illness). Avoid arguing about the reality of their delusions or hallucinations. Instead, focus on the real-world consequences, like 'I can see this is causing you a lot of distress' or 'I'm worried about you not being able to work.' Express concern and encourage them to see a doctor for the distress itself, rather than the symptoms they don't believe are real.

4. Are people experiencing psychosis always violent?

No. This is a harmful stereotype often amplified by media. The vast majority of people with serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia are not violent. In fact, they are far more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators. Violence is not a symptom of psychosis itself, though the risk can increase if the person is not receiving treatment and is experiencing paranoid delusions.

References

camh.ca — Early Warning Signs of Psychosis

latimes.com — Nick Reiner Was Prescribed Schizophrenia Medication Before Killings