The Laughter That Fills a Silent Room

It’s a familiar scene. The tension at the dinner table is thick enough to cut with a knife. Someone says something awkward, and in that vacuum of silence, you swoop in. A perfectly timed, self-deprecating joke lands. The tension breaks. Everyone laughs, relieved. You’re the hero of the moment.

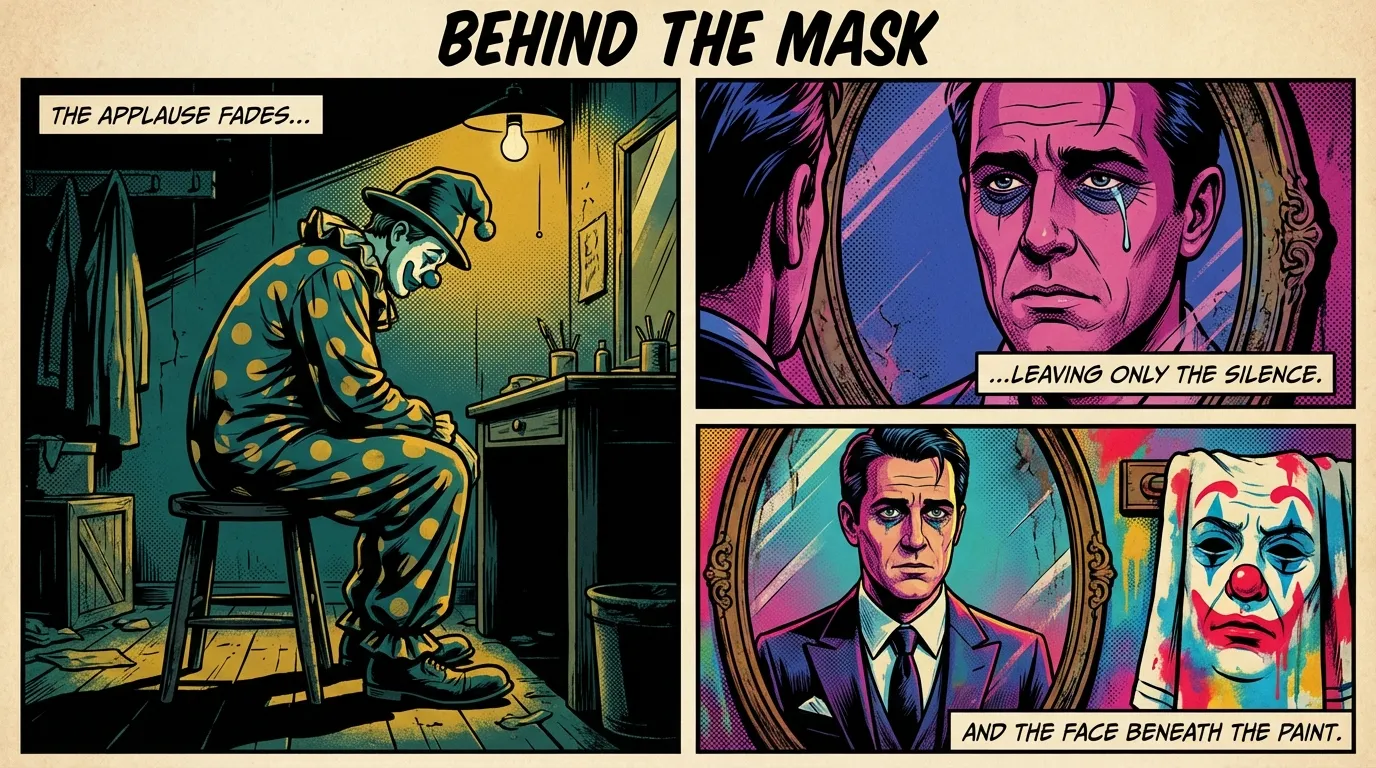

But later, alone in your room, the echo of that laughter feels hollow. The relief you provided for others never quite reaches you. This role—the funny one, the class clown, the person who can always lighten the mood—is both a gift and a cage. For many, it's the most sophisticated form of using humor as a defense mechanism.

We see it in cultural icons like Adam Sandler, who built a career on a persona that blends goofy antics with a palpable undercurrent of melancholy. The humor is loud, but the feeling it often masks is quiet. This isn't about losing your sense of humor; it’s about asking a brave question: is your laughter a bridge connecting you to others, or is it a wall keeping your true feelings locked inside?

The Double-Edged Sword: When the Class Clown Cries Alone

Before we go any further, let's hold one truth up to the light: that impulse to make people laugh, to ease their discomfort, comes from a deeply kind place. It's your heart's attempt to create harmony and connection. That's not a flaw; that's your courage on display.

But Buddy, our emotional anchor, would gently ask you to notice the cost. Being the designated 'funny one' can be incredibly lonely. There's a constant, humming pressure to perform. You might feel that your value in the group is tied directly to your wit, and that if you were to show up with just your sadness or your anxiety, you wouldn't be welcome.

This is the painful paradox of hiding depression with jokes. You become the architect of a space where everyone else gets to feel good, but there's no room for your own authentic pain. This pattern of emotional avoidance doesn't make you weak; it means you've been strong for a very, very long time. The act of constantly using humor as a defense mechanism is exhausting. Your desire for genuine connection is the most honest thing about you, even when it's wrapped in a punchline.

Protector or Saboteur? Identifying Your Humor Style

Now, let’s look at the underlying pattern here. As our sense-maker Cory would say, this isn't random; it's a system. Your humor is a tool. The critical question is what kind of tool it is and what job you’re using it for. Using humor as a defense mechanism isn't a single action, but a category of behaviors.

To understand this, we can turn to the psychology of humor itself. Research outlined in Psychology Today defines four primary styles, two of which are generally positive and two of which can become problematic.

1. Affiliative Humor: This is the glue. You tell jokes, say funny things, and engage in banter to bring people together and build relationships. These are the affiliative humor benefits we cherish; they create intimacy and joy.

2. Self-Enhancing Humor: This is about maintaining a humorous outlook on life, even when things are difficult. It's a healthy coping mechanism for stress, allowing you to find amusement in life's absurdities without hurting yourself or others.

3. Aggressive Humor Style: This involves sarcasm, teasing, and ridicule at the expense of others. While it can sometimes create bonds within an 'in-group', it often serves to alienate and wound.

4. Self-Defeating Humor: This is the classic self-deprecating humor where you put yourself down to get a laugh and gain approval from others. While occasionally endearing, it can, over time, erode your self-esteem and signal to others that it's okay not to take you seriously.

When humor becomes a problem, it's often because we're relying too heavily on the last two styles as our primary coping mechanisms for stress. Cory’s take is clear: you first need to identify your dominant style before you can decide if it's truly serving you. You have permission to analyze your patterns without judgment. This is just data collection.

How to Keep the Joy, But Let in the Feeling

Alright, you have the data. You see how consistently using humor as a defense mechanism has created a gap between how you feel and what you show. Our strategist, Pavo, would say, 'Awareness is step one. Strategy is step two. Here is the move.'

The goal isn't to stop being funny. That's part of who you are. The goal is to expand your emotional vocabulary and your communication toolkit so that humor is a choice, not the only option.

Here's a simple, strategic plan:

Step 1: Introduce the 'And' Statement. You don't have to replace humor with raw vulnerability overnight. You can blend them. Instead of saying, 'I'm fine!' with a joke, try this script: 'Things are a bit stressful right now, and I'm also trying to find the humor in it.' The 'and' makes space for both truths to exist.

Step 2: Test the Waters with a Safe Person. Identify one person in your life—a partner, a sibling, a best friend—who has earned the right to hear your real feelings. Before your next conversation, set an intention to share one small, honest feeling without immediately covering it with a joke.

Step 3: Script Your Vulnerable Opener. Pavo insists on preparation. Having a line ready reduces anxiety. Try one of these: 'Hey, can I be serious for a second?' or 'I know I usually make a joke about this stuff, but it's actually been on my mind.' This signals to the other person that you're changing the mode of conversation, giving them a chance to meet you there.

This isn't about abandoning a skill that has protected you. It's about building new pathways for connection so that the funny, brilliant you and the vulnerable, real you can finally be the same person in the same room.

FAQ

1. What's the difference between a good sense of humor and using humor as a defense mechanism?

A healthy sense of humor is a tool for connection and resilience (affiliative and self-enhancing styles). Using humor as a defense mechanism becomes a problem when it's a form of emotional avoidance—consistently using jokes to deflect from genuine feelings, prevent intimacy, or cope with pain you're not addressing.

2. Can self-deprecating humor ever be healthy?

In small doses and among trusted friends, self-deprecating humor can show humility and be relatable. However, when it becomes your primary mode of communication (a self-defeating style), it can damage your self-esteem and signal to others that you don't need to be taken seriously, which can be detrimental in the long run.

3. How can I support a friend who I think is hiding their depression with jokes?

The key is to create a safe space without pressure. You can laugh at their jokes but also gently acknowledge the topic underneath. Try saying something like, 'That's funny, but it also sounds like that situation was genuinely frustrating. How are you really doing with it?' This validates their humor while opening a door to a more serious conversation if they choose to walk through it.

4. Is it bad to use humor to cope with stress?

Not at all. Using self-enhancing humor to find perspective and levity in stressful situations is a powerful and healthy coping skill. It only becomes a concern when it's the only tool you use, preventing you from actually processing the source of the stress or seeking support from others.

References

psychologytoday.com — The 4 Styles of Humor