The Contradiction You Can Feel in Your Bones

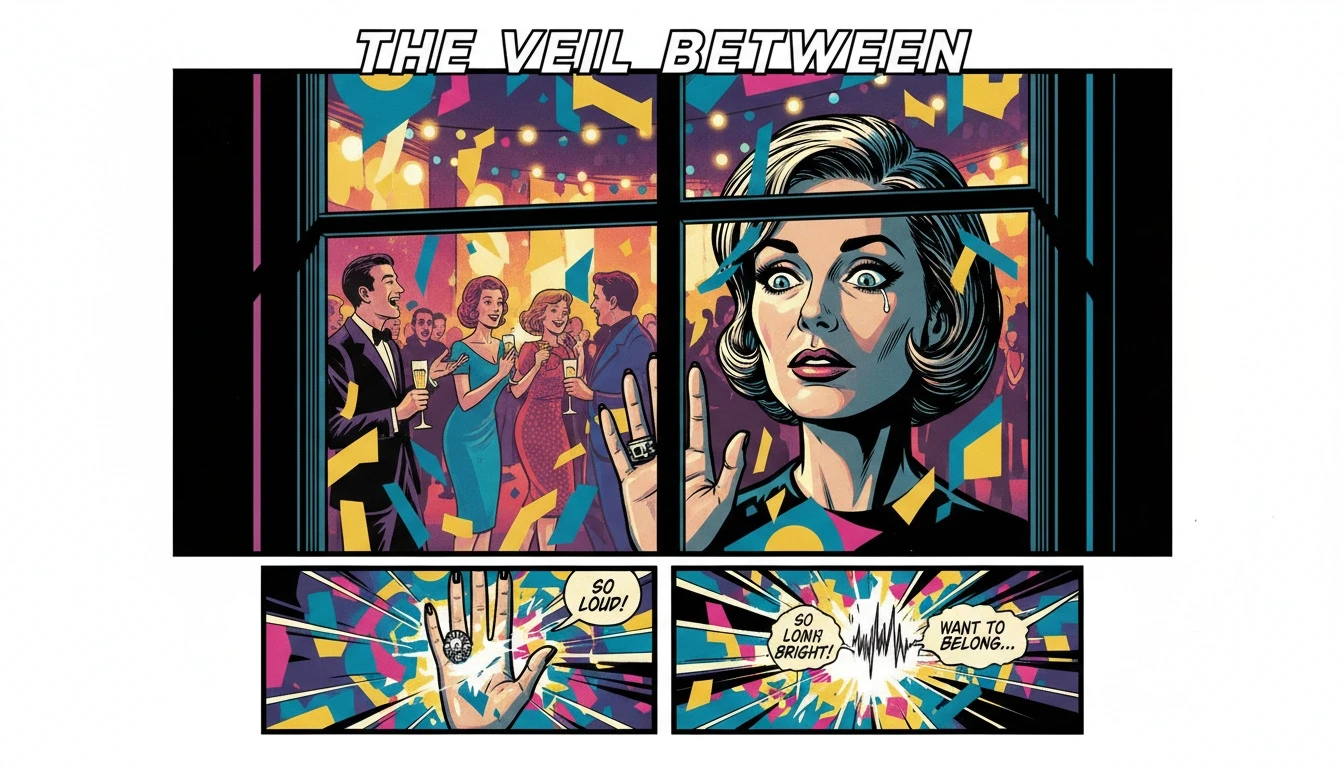

The party is a physical presence. The bass thumps in your chest, a hundred conversations blur into a wall of sound, and the flashing lights feel like they’re rewriting your brain's code in real-time. Every sensory receptor is screaming for a quiet, dark room. And yet, a deeper part of you feels… energized. You want to be here. You crave the connection humming in the air.

This is the exhausting paradox for the neurodivergent extrovert. You are pulled toward the very thing that can overwhelm you. For years, the popular understanding of autism has been flattened into a simple, incorrect stereotype: the quiet, withdrawn loner who prefers solitude. This leaves those who experience both autism and extraversion feeling like a glitch in the system, profoundly misunderstood by a world that loves neat little boxes.

The Pain of the Paradox: When Your Brain and Personality Clash

Let's just sit with that feeling for a moment. It’s a specific kind of loneliness, isn’t it? It’s like standing outside a warm, brightly-lit house in the freezing cold. You can see the laughter and connection inside, and every part of you wants to join in, but you can't seem to find the right key for the door. This is one of the core autistic extrovert struggles: a deep, innate desire for connection met with social difficulties.

You might feel alienated from neurotypical peers who navigate social nuance with an ease that feels foreign. At the same time, you might feel out of place in some neurodivergent spaces where socializing is seen as a burden, not a source of energy. That feeling isn't a flaw in you; it’s a testament to your brave desire to be loved and understood.

As our emotional anchor Buddy would say, “That exhaustion isn’t a sign you’re failing at being social; it’s a sign of how hard you’re fighting to honor your need for people.” The constant mental calculus of navigating social communication challenges while managing your internal state is incredibly taxing. It's the emotional labor of 'masking in autism' not just to fit in, but to get the very connection you need to recharge.

Debunking the Stereotype: How Autism and Extraversion Can Co-exist

Alright, let's cut through the noise. Here’s the reality check you deserve. Autism is not a personality trait. It’s a neurotype—a fundamental difference in how your brain is wired to process information, communication, and sensory input. Extraversion, on the other hand, is about how you gain and expend energy. An extrovert recharges their battery by being around people.

They are not mutually exclusive. They simply operate on different axes. As our realist Vix would put it, "Thinking an autistic person can't be an extrovert is like thinking someone who is colorblind can't enjoy art. They're just experiencing it through a different filter." The confusion arises because the external signs of autistic sensory overload—withdrawing, going non-verbal, needing to escape—look identical to introversion from the outside.

But the internal motivation is completely different. An introvert leaves the party because they are drained and need solitude to recharge. An autistic extrovert might leave the party because their processing unit has crashed from a sensory overload in social situations, even though they were still psychologically craving the interaction. Research and anecdotal evidence increasingly validate the experience of the extroverted autistic person, challenging outdated views on Asperger's and sociability. The intersection of autism and extraversion is not a contradiction; it’s a specific neuro-social reality.

Strategies for Thriving as a Neurodivergent Extrovert

Understanding the dynamic is the first step. The next is building a strategy. As our social strategist Pavo insists, you don't have to be a passive victim of your wiring. You can design a life that accommodates both your need for people and your brain’s processing limits. Here is the move:

Step 1: Curate Your Social Arena.

Stop forcing yourself into environments that guarantee a system crash. Loud, unstructured clubs or crowded bars are high-risk for sensory overload. Instead, seek structured social events: a board game night, a book club, a hiking group, a pottery class. These provide a focal point beyond just small talk and offer a more controlled sensory experience.

Step 2: Master the Energy Budget.

Treat your social energy like a bank account. An upcoming wedding or big party is a major withdrawal. You need to make deposits beforehand (time alone, engaging in special interests) and schedule a recovery day afterward with zero social obligations. This includes planning for stimming to regulate social energy—it's not a weird tic; it's a vital self-regulation tool.

Step 3: Deploy Strategic Scripts.

Pavo’s signature move is having a pre-written script to reduce cognitive load in the moment. You don’t need to improvise everything. Having a few phrases ready can be a lifeline.

For entering a group: "This looks like a fun conversation, mind if I join? What are you all discussing?"

For explaining a need: "I’m really enjoying this, but I need to manage my sensory input. I'm going to step out for five minutes to get some quiet."

* For leaving: "It was so great catching up! I've hit my social limit for the night, so I'm heading out, but let's connect again soon."

These strategies aren't about masking your true self. They are about creating a sustainable framework for your autism and extraversion to coexist, allowing you to get the connection you crave without paying for it with burnout.

FAQ

1. What does it feel like to have both autism and extraversion?

It often feels like a contradiction. You genuinely crave social interaction and feel energized by people (extraversion), but the mechanics of socializing—reading cues, managing sensory input, and small talk—can be confusing and exhausting (autism). This can lead to a cycle of seeking connection, getting overwhelmed, retreating to recover, and then feeling lonely again.

2. How can I manage sensory overload at social events I truly want to attend?

Strategic management is key. Plan ahead: arrive early before it gets too loud, identify a quiet space you can retreat to (like a patio or hallway), use discreet sensory tools like noise-reducing earplugs, and set a time limit for yourself. Don't be afraid to leave when you feel your system getting overloaded, even if you're still enjoying the company.

3. Is masking a good or bad thing for an autistic extrovert?

Masking is a complex tool. It can be a useful, conscious strategy to navigate specific social situations and achieve a desired outcome (like getting through a job interview). However, when it becomes an unconscious, constant performance out of fear of rejection, it leads to severe burnout and a lost sense of self. The goal is to reduce compulsive masking and use it only as a deliberate, short-term strategy when necessary.

4. Why is the stereotype of the 'introverted autistic' so persistent?

The stereotype persists because the outward behaviors of an autistic person experiencing social processing difficulties or sensory overload (e.g., withdrawing, avoiding eye contact, needing to be alone) look very similar to the behaviors of a neurotypical introvert who is socially drained. Observers misinterpret the reason for the behavior, confusing a system overload with a personality preference for solitude.

References

psychologytoday.com — The Extroverted Autistic Person - Psychology Today

reddit.com — As a person with high functioning autism, I think I'm an extrovert - Reddit