Change Feels Like Loss Because You’re Not Just Changing Your Life—You’re Changing Your Belonging

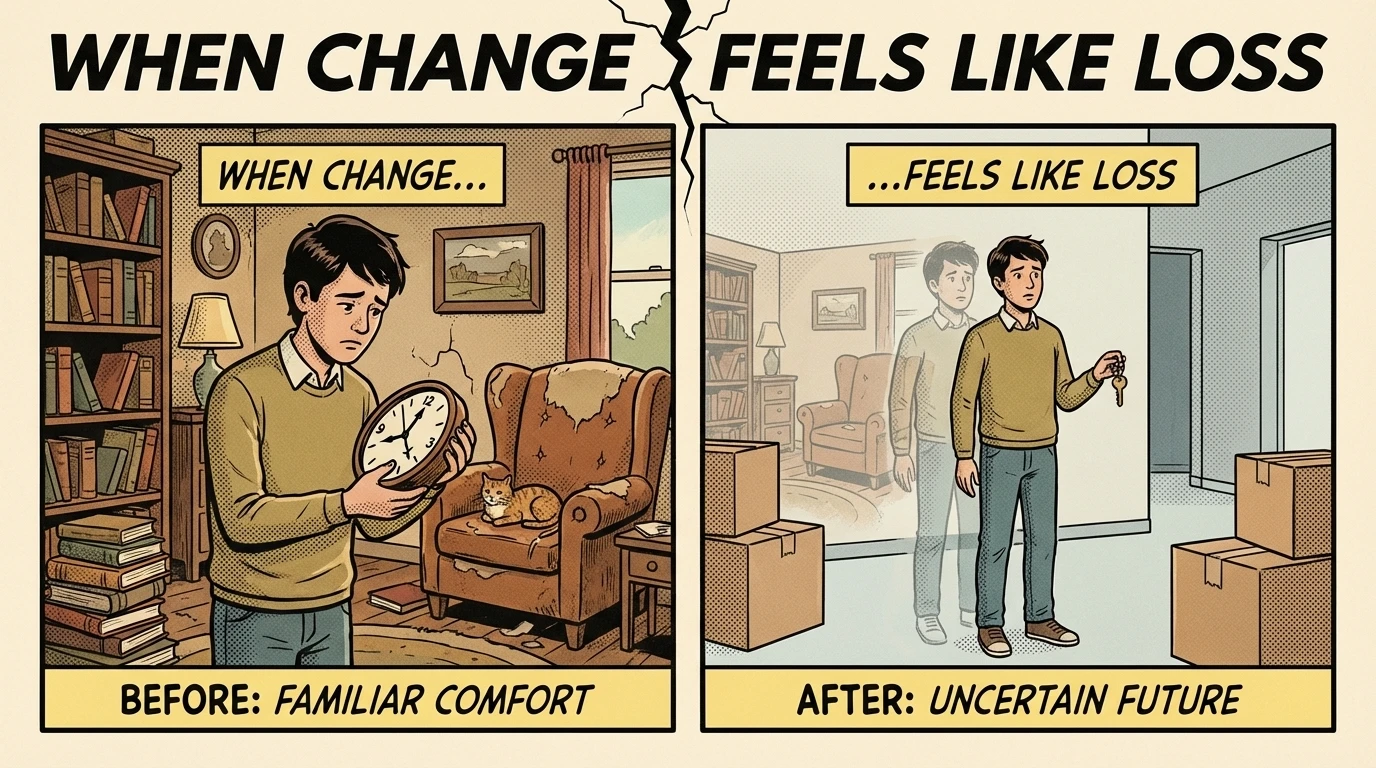

There’s a particular moment that happens in adult growth that nobody warns you about: the point where your old life still exists, but it no longer feels like home.

It’s not dramatic. It’s quieter than that. You’re still in the same city, the same group chat, the same job title, the same family system. Yet something in you has shifted, and now you can’t comfortably participate in the old emotional economy. The jokes land differently. The dynamics feel louder. Your tolerance drops. Your “fine” stops being effortless.

This is why change feels like loss. Growth doesn’t only add; it subtracts. It takes away the familiar roles that gave you a sense of belonging—even if those roles were painful.

Sometimes the role was “the easy one,” the one who didn’t need much.

Sometimes it was “the fixer,” the one who kept everyone stable.

Sometimes it was “the strong one,” the one who didn’t get messy.

Sometimes it was “the chill one,” the one who never made things awkward by having boundaries.

When you evolve, you may lose the social rewards that came with those roles. People might resist your change not because they want you miserable, but because your old self fit the system. Your growth disrupts the equilibrium.

This is the part of personal growth that doesn’t sound inspirational: you can become healthier and still feel lonelier for a while.

And if you’ve ever wondered, Why do I feel sad even though I’m doing the right thing?—that sadness is not a sign you’re going backwards. It’s a sign you’re losing a form of belonging you once depended on.

The “Grief” of Growth Is Real—even When Nothing “Bad” Happened

Most adults know how to grieve obvious losses: a breakup, a death, a job ending, a friendship exploding. But the grief that comes with inner change is subtler. It’s the grief of leaving a familiar self, and it can feel confusing precisely because there’s no clear external event to point to.

You can grieve:

- the version of you who believed certain people would change

- the dream you outgrew

- the identity you built to survive

- the coping strategy that once protected you, even if it harmed you later

- the old intensity that substituted for love

- the old ambition that substituted for worth

- the old numbness that substituted for safety

In grief theory, a helpful frame is that grief is not only about death; it’s about attachment and meaning. When something you were attached to—an identity, a narrative, a relationship pattern—no longer fits, your system experiences that as loss.

This is why personal growth can feel physically heavy. Your appetite shifts. Your sleep gets weird. Your motivation fluctuates. You feel tender in places you didn’t know existed.

If you want a mainstream mental health framing: grief and adjustment reactions often involve emotional, cognitive, and physical symptoms, even when the “loss” isn’t socially recognized. Resources like the American Psychological Association’s overview on grief and the NHS guidance on grief and loss are useful entry points for understanding why grief can be broad, not just literal bereavement.

But beyond references, here’s the lived truth: when you change, you don’t just gain a new life—you lose the old internal story that explained who you were.

And losing a story hurts, even if the story was limiting.

Why Letting Go Can Feel Like Betraying Yourself

One of the most emotionally brutal parts of growth is this: the thing you’re letting go of once saved you.

People talk about “bad habits” and “toxic patterns” as if they appeared randomly. But most patterns started as solutions. They were adaptations to earlier environments.

Perfectionism often began as a way to avoid criticism.

People-pleasing often began as a way to stay safe in volatile relationships.

Hyper-independence often began as a way to avoid disappointment.

Numbing often began as a way to survive pain you couldn’t process.

So when personal growth asks you to release these strategies, it can feel like betrayal: If I let this go, who am I? What protects me?

That’s why change feels like loss from the inside. You’re not only letting go of behaviors—you’re letting go of your old protection system.

And the mind panics, not because it prefers suffering, but because it prefers familiarity. Your nervous system reads familiar pain as predictable, and predictable as safer than uncertain freedom.

This is also why adults sometimes “relapse” into old patterns at the exact moment life starts improving. Not because they’re self-sabotaging in a cartoonish way, but because improvement introduces uncertainty. New standards. New expectations. New vulnerability.

Growth asks you to step into a life where you can’t pre-script the outcome. If your inner world is trained to equate uncertainty with danger, you will grieve the old control—even if it was control through self-denial.

That grief doesn’t mean you should go back. It means you’re human.

The Loneliness of Evolving: When Your Old Relationships Don’t Fit Your New Boundaries

There’s a particular loneliness that arrives when you begin to heal: you realize how many relationships were held together by your self-erasure.

You stop overexplaining.

You stop apologizing for existing.

You stop tolerating “jokes” that are actually contempt.

You stop performing emotional availability for people who never reciprocated it.

From the outside, this can look like confidence. From the inside, it can feel like loss—because it often comes with social consequences.

Some people won’t like the new version of you. Not because you became worse, but because you became less accessible. Less easily managed. Less predictable.

And this is where a lot of adults get emotionally ambushed: growth makes you more honest, but honesty can temporarily reduce connection. You start seeing which relationships are built on mutuality versus convenience.

That can be heartbreaking. Because sometimes you don’t “break up” with a friend; you simply outgrow the dynamic. The contact fades. The emotional depth disappears. You become polite strangers who still technically care about each other.

If you’ve ever felt guilty for “changing,” you’re not alone. Many adults internalize the idea that evolving is a kind of betrayal. But healthy growth isn’t an attack. It’s an alignment.

Still, alignment comes with grief.

For an accessible mental-health resource on self-esteem, boundaries, and relational dynamics, organizations like Mind (UK) provide helpful context around how relationship patterns interact with wellbeing. It’s not a substitute for personal experience—but it validates a key point: inner change often reverberates socially.

This is the emotional paradox of personal growth: you become more yourself, and for a while you may feel less held.

The Turning Point: When You Learn to Mourn and Move at the Same Time

A lot of people delay growth because they believe it should feel clean. They’re waiting for an internal green light: I’ll change when I no longer feel attached to the old life.

But that’s not how it works.

Adults don’t usually “finish” grieving before they move forward. They do both at once. They mourn and move. They carry tenderness and still choose the boundary. They miss the old version of themselves and still refuse to return.

This is the quiet maturity that doesn’t show up on social media: the ability to hold conflicting emotions without interpreting the conflict as failure.

You can miss someone and still know they are not safe for you.

You can miss a dream and still accept it no longer fits who you are.

You can grieve the old intensity and still choose calm.

You can feel lonely in your growth and still trust it.

That’s what resilience looks like in adulthood: not relentless optimism, but emotional range without self-abandonment. If you want a reputable overview of resilience as an adaptive process, the APA’s resilience resources are a solid grounding point.

But the deeper truth is personal: when you stop treating grief as a warning sign, change becomes easier to sustain. You stop interpreting sadness as “wrong.” You start seeing it as a normal cost of evolving.

And then something subtle happens. The loss begins to feel less like punishment and more like passage.

Not because it stops hurting—but because it starts making sense.

FAQ

Why does personal growth make me feel sad?

Because growth often involves loss: old identities, coping strategies, relationship dynamics, and familiar narratives. Sadness can be a normal grief response to evolving—even when the change is healthy.

Is it normal to feel lonely when I’m changing for the better?

Yes. When you change boundaries or self-concept, some relationships may no longer fit. The transition can feel isolating before new belonging forms.

Why do I miss things that were bad for me?

Because you can miss familiarity, not just goodness. Many patterns were once protective, and letting them go can feel like losing safety—even if the pattern harmed you later.

How do I know if I’m grieving or making the wrong decision?

Grief often includes longing and sadness, but a wrong decision often includes persistent self-erasure, dread, or loss of integrity. If you feel sorrow and self-respect, that’s often grief—not a mistake.

Can therapy help with this “change feels like loss” experience?

Yes. Therapy can help you process grief, identity shifts, attachment patterns, and boundary guilt—especially when your old coping strategies were formed in earlier relational environments.

References

- American Psychological Association – Grief

- American Psychological Association – Resilience

- NHS – Bereavement, grief and loss

- Mind (UK) – Mental health information & support

- Greater Good Science Center – Emotions, meaning, and wellbeing