The Echo in the Room: The Lingering Trauma of a Controlled Life

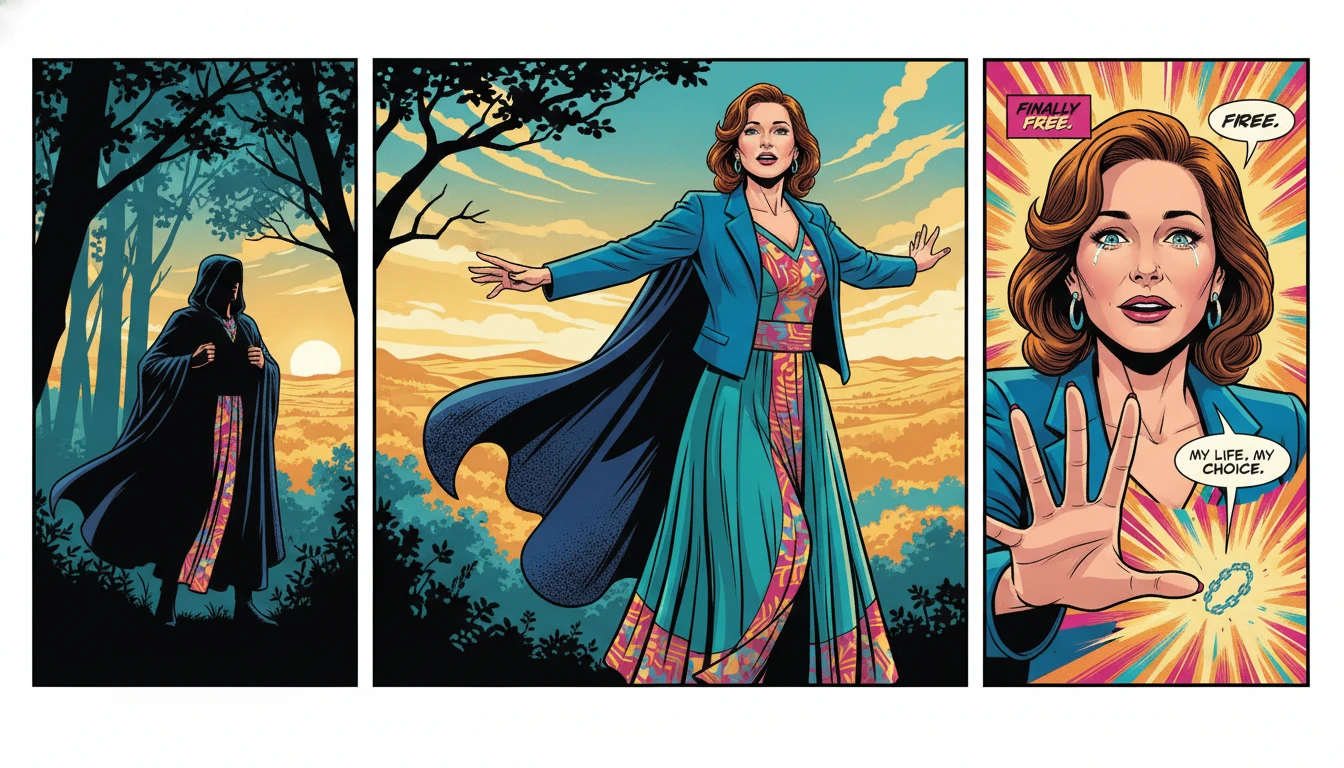

It’s a quiet Tuesday afternoon. You’re making coffee, and a specific phrase, a song, or even a particular slant of light hits you, and suddenly you’re not in your kitchen anymore. You’re back there. The rules, the certainty, the crushing weight of a belief system that was not your own but became the very architecture of your mind. This is the quiet, haunting reality of life after leaving a cult or a high-control group.

When celebrated actor Glenn Close speaks about growing up in the Moral Re-Armament (MRA), she describes a complete loss of self, a feeling of being unable to have any of her own thoughts. It’s a chillingly familiar experience for survivors. The world sees a brilliant artist, but underneath lies the story of a young person whose personal autonomy was systematically dismantled. Her journey highlights a crucial truth: the exit is not the end of the story. The real work is in the slow, painstaking process of recovering from a high control group.

This isn't about dramatic deprogramming scenes from movies. It’s about the subtle, daily work of untangling your thoughts from doctrine, your emotions from programmed responses, and your identity from the collective. It's a path of rebuilding identity after trauma, and it requires immense patience and self-compassion.

Deconstructing the Aftermath: Why It Still Hurts

As our mystic, Luna, would say, think of your experience like a tree that was forced to grow around a stone. On the outside, you might look whole, but your roots were diverted. They learned to twist and bend to survive. Leaving the group is like removing the stone; it leaves a void, a shape of what was once there. The pain you feel is the tree learning to send roots into that empty space, to reclaim its natural form.

The psychological effects of cults are not simple; they often manifest as Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD), a condition born from prolonged, repeated trauma where escape felt impossible. It’s the chronic anxiety, the difficulty trusting your own judgment, the feeling of being fundamentally different from everyone else. Your nervous system was marinated in a state of high alert and rigid compliance.

Luna encourages us to see this not as damage, but as a map. Where does the ache live in your body? That is where your attention must go. The process of recovering from a high control group is not about erasing the past, but about integrating its lessons. It’s a spiritual winter, a necessary fallow period where you gather the strength to bloom again on your own terms.

Here is your internal weather report: What is the emotional climate inside you right now? Is it foggy with confusion? Stormy with anger? Or is there a small patch of sun trying to break through? Just notice, without judgment. This is the first step in life after leaving a cult—learning to trust your own sky again.

Recognizing the Patterns of Control

Our analyst, Cory, approaches this from a place of clarity. He’d sit you down, look you in the eye, and say, “Let’s look at the underlying pattern here. This was not random, and it was not your fault. It was a system.” Recovering from a high control group requires shifting from self-blame to systemic analysis.

High-control groups operate on a predictable playbook of psychological manipulation. They isolate you from outside influences, create an 'us vs. them' mentality, demand absolute obedience, and control the flow of information. Your thoughts were not your own because the environment was designed to prevent independent thought. This is the core of deprogramming the mind: recognizing the external architecture that was built inside your head.

Thinking this way helps in re-establishing personal autonomy. You weren't weak for believing; you were a human who responded to powerful, sustained psychological pressure. Glenn Close spoke of the guilt and trauma that took her years to work through. This is a common and profound part of the journey.

Cory wants to offer you this today:

You have permission to be angry at the system that took your youth. You have permission to grieve the person you might have become without this experience. You have permission to untangle your worth from their doctrine, slowly and imperfectly. The process of recovering from a high control group is an act of profound intellectual and emotional rebellion.

A Gentle Path to Reclaiming Your Identity

“Okay,” our strategist Pavo would say, pulling out a notepad. “Feeling is essential. Analyzing is crucial. Now, what’s the move?” For Pavo, recovering from a high control group is about converting insight into action, no matter how small. It’s about a deliberate strategy for rebuilding identity after trauma.

Your autonomy wasn't taken in one grand gesture; it was eroded through a thousand tiny concessions. Reclaiming it works the same way, in reverse. The goal isn't to suddenly become a new person. The goal is to make one sovereign choice today. And then another tomorrow. As the CDC notes in its guidance on traumatic events, re-establishing a sense of safety and control is paramount.

Here is a gentle, pragmatic action plan for re-establishing personal autonomy:

Step 1: Curate Your Information Diet.

For today, choose one article to read, one podcast to listen to, or one show to watch that has absolutely nothing to do with the group or its ideology. Choose it simply because you are curious. This is you reclaiming control over what enters your mind.

Step 2: Make a 'Pointless' Sensory Choice.

Buy a type of tea you've never tried. Wear a color you were told was inappropriate. Listen to a genre of music that was forbidden. The choice itself doesn't matter; what matters is that you are the sole authority on your own preference. This is a micro-dose of self-trust.

Step 3: Practice the 'Neutral Observation'.

When you feel a programmed thought or emotion arise (like guilt or fear), don't fight it. Pavo's script is simple: Say to yourself, “I notice I am feeling the sensation of guilt. This is a leftover pattern.” By naming it instead of embodying it, you create a sliver of space between you and the programming. That space is where your true self begins to grow again. The journey of recovering from a high control group is won in these small, quiet moments of self-advocacy.

FAQ

1. What is C-PTSD and how does it relate to being in a high-control group?

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) stems from prolonged, repeated trauma where the victim feels trapped. Unlike PTSD from a single event, it deeply affects one's sense of self, emotional regulation, and relationships, which is why it's common among those recovering from a high control group.

2. How long does recovering from a high control group typically take?

There is no set timeline. Recovery is a non-linear process that can take years, and its pace depends on the individual, the duration of their involvement, their support system, and access to professional help. Patience and self-compassion are key.

3. What are the first steps to rebuilding my identity after leaving a cult?

Start small. Focus on re-establishing personal autonomy through tiny choices. Explore new hobbies, listen to different music, read widely, and allow yourself to form opinions without external validation. Reconnecting with your personal preferences is a foundational step.

4. Why do I sometimes miss parts of my life in the group?

It's very common to miss the sense of community, purpose, and certainty the group provided. This is a form of grief and doesn't invalidate the harm you experienced. Acknowledging these complex, conflicting feelings is a normal part of the healing process.

References

cdc.gov — Coping with a Traumatic Event - CDC

time.com — What It’s Like to Grow Up in a Cult - TIME