That Nagging Doubt: 'Is This All Just Made Up?'

If you’ve taken the Myers-Briggs, felt that jolt of recognition, and then immediately felt a wave of doubt—you are not alone. It’s that strange feeling you get from a well-written horoscope; is this a profound insight, or is it just vague enough to feel personal? That quiet voice questioning the whole thing isn't cynicism; it's your sharp intellect at work.

As our emotional anchor, Buddy, always reminds us, validating your own intuition is the first step. That feeling of skepticism is valid. You’re right to question any tool that claims to map your inner world. This is especially true for systems that can feel like they're putting you in a box, a feeling often associated with what’s known as the Barnum effect in personality tests.

So let's give that doubt a safe space. The desire for a personality framework is deeply human; we want to understand ourselves and our place in the world. But that doesn't mean we have to accept these frameworks without question. The debate around the Myers-Briggs Test scientific validity is not just academic noise; it’s a crucial conversation about what we accept as truth about ourselves.

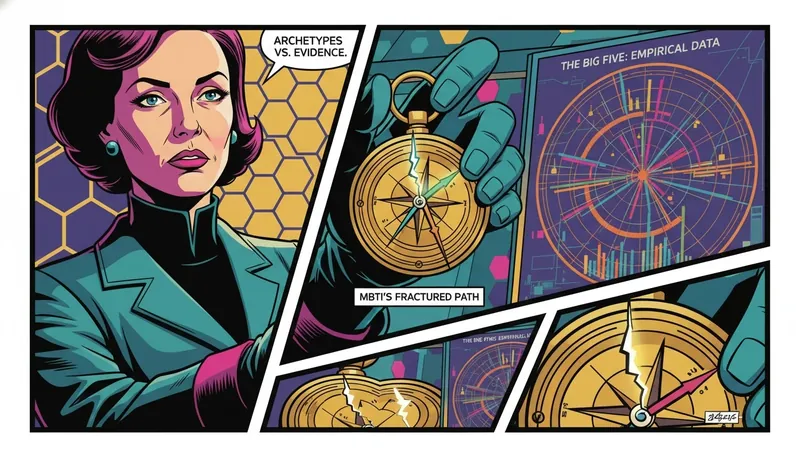

The Scientist's Case Against MBTI: Reliability, Validity, and Binaries

Alright, let's get our realist, Vix, in here to perform some reality surgery. She'd tell you to put the warm feelings aside for a moment and look at the facts. The academic and psychological communities have significant, long-standing mbti criticism.

The first major issue is its poor test-retest reliability. In simple terms, if a test is reliable, you should get roughly the same result every time you take it. Studies have shown that as many as 50% of people get a different result when retaking the MBTI just five weeks later. If your core personality can supposedly flip from Introvert to Extrovert in a month, the test isn't measuring a stable trait; it's measuring a mood.

Second, the test creates a false dichotomy. You are either an Extrovert or an Introvert, a Thinker or a Feeler. There is no middle ground. Most human traits, however, exist on a spectrum. As noted by critics like Adam Grant in publications such as Psychology Today, most people are ambiverts, not pure extroverts or introverts. Forcing people into one of two boxes is a fundamental flaw that compromises the Myers-Briggs Test scientific validity.

Then there's the lack of empirical evidence and its questionable origins. The MBTI was developed by Katharine Briggs and Isabel Myers, who were not formally trained psychologists. While their work was based on Carl Jung's theories, it was their interpretation, not a rigorously tested scientific model. This leads directly to the core charge: is mbti pseudoscience? In a formal, academic sense, many psychologists would argue yes, because it doesn't meet the standards of validity and reliability.

Because of these problems with myers-briggs, the academic world largely prefers a different model: the Big Five personality traits (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism). This model is empirically derived, shows better reliability, and, as extensive research like this study from NCBI shows, is better at predicting life outcomes. The ongoing debate over the Myers-Briggs Test scientific validity often concludes with the Big Five being presented as the more robust alternative.

So, Is It Useless? How to Use MBTI as a Tool, Not a Dogma

So, Vix has laid out the case for the prosecution, and it's a strong one. Does that mean we throw the entire concept in the trash? Not if you're a strategist. Our pragmatist, Pavo, would argue that a tool's usefulness depends entirely on how you use it. Knowing the Myers-Briggs Test scientific validity is weak doesn't render it useless; it simply clarifies its function.

Here is the strategic move: Stop treating the MBTI as a diagnostic machine and start using it as a conversation starter. It’s not a label carved in stone; it’s a language for talking about preferences.

Step 1: Use It as a Language, Not a Label.

Instead of saying "I'm an INTJ," try saying, "I often prefer to process information internally and look for logical patterns." The first is a rigid identity; the second is a flexible description of a preference. This approach helps you avoid the false dichotomy trap and use the concepts to build self-awareness without being limited by them.

Step 2: Focus on Improving Communication and Empathy.

The greatest value of the MBTI might be in understanding that other people have fundamentally different operating systems. If you identify as a "Thinker," it can be a powerful realization that your partner or colleague isn't being irrational; they may simply be leading with a "Feeler" preference that prioritizes group harmony and emotional context. It's a framework for empathy, not a weapon for arguments.

Step 3: Treat It as a Starting Point for Deeper Exploration.

If your result resonates, don't stop there. Ask why. What experiences shaped this preference for structure (Judging) or spontaneity (Perceiving)? Acknowledging the low Myers-Briggs Test scientific validity frees you to use it as a prompt for journaling and self-reflection rather than accepting it as a final answer. It’s one clue among many, not the entire solution to the puzzle of you.

FAQ

1. Why do so many psychologists criticize the Myers-Briggs test?

The main criticisms focus on its poor scientific grounding. This includes low test-retest reliability (people often get different results), its use of false dichotomies (e.g., you're either an introvert or extrovert, with no middle ground), and a general lack of empirical evidence to support its claims of predicting behavior or job success.

2. What is a more scientifically accepted personality test than the MBTI?

The most widely accepted model in academic psychology is the Big Five personality traits, also known as the OCEAN model (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism). It is based on empirical research, demonstrates higher reliability, and is a better predictor of life outcomes.

3. Is the Myers-Briggs test considered pseudoscience?

From a strict scientific standpoint, many psychologists categorize it as pseudoscience because it lacks the empirical validity and reliability required of a psychological instrument. While it can be a useful tool for self-reflection, it is not considered a scientific measure of personality.

4. Can my Myers-Briggs type change over time?

Yes, and this is a central part of the criticism against it. Because of its low test-retest reliability, it's common for individuals to get different four-letter results when they take the test months or years apart, questioning whether it measures a stable, innate personality type.

References

psychologytoday.com — The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov — The Big Five Personality Traits