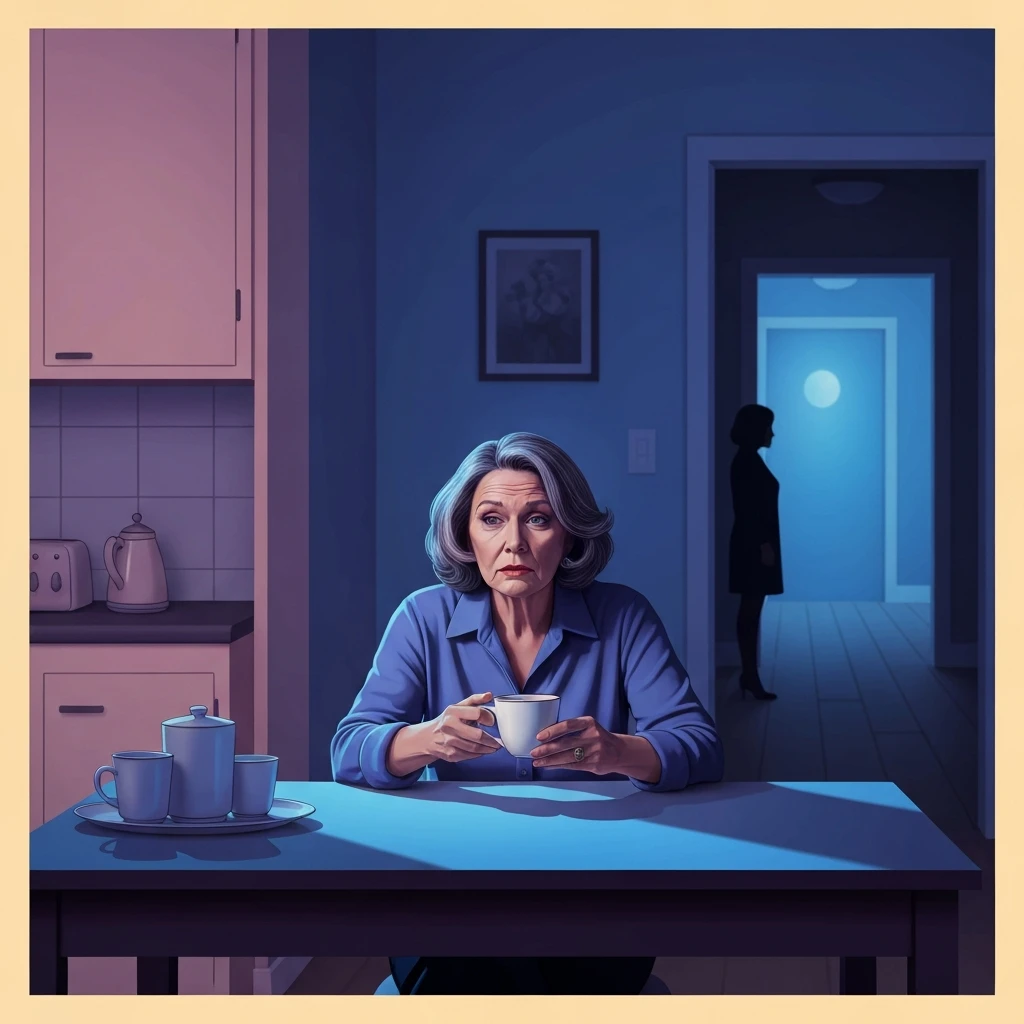

The Heavy Silence of the Role Reversal

It starts with a phone call at an hour that feels like a threat, or perhaps a sharp remark over a dinner you spent two hours preparing. You realize the person who once protected you has become a stranger who now demands protection, yet fights your every effort to provide it. This is the visceral reality of caring for difficult elderly parents, a role that often feels less like an act of love and more like a slow erosion of your own identity.

You aren't just managing medications; you are managing a history of unresolved trauma, personality changes in aging parents, and the specific, bone-deep fatigue that comes from being a target for someone you are trying to save. The search for help usually begins with a practical question about logistics, but deep down, it’s an identity reflection: How do I remain a good person while my parent makes it impossible to be a happy one? To move from this place of emotional overwhelm toward a sustainable path, we must first look at the mechanics of why their behavior has become so volatile.

Why Your Parent Isn't the Person They Used to Be

When we look at the underlying pattern here, we have to acknowledge that the human brain in decline often loses its filter before it loses its function. If you are dealing with irrational elderly behavior, it is rarely a conscious choice to be cruel. Neurologically, the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for empathy and impulse control—is often the first to thin. This means that a parent who was always a bit stubborn might now become aggressively defiant, or those with narcissistic aging parents may find that their parent's need for control has shifted into a desperate, frantic high gear.

This isn't random; it's a cycle of fear. As their world shrinks, their need to dominate their immediate environment—which usually means you—expands. By naming this dynamic, we can stop taking the bait. You are not failing them; you are witnessing a biological process that has stripped them of their social graces.

Your Permission Slip: You have permission to view their behavior as a symptom rather than a personal indictment. You are allowed to observe their outbursts with the detached clinical eye of a researcher, knowing that their lack of gratitude is a reflection of their neurological state, not your worth as a child.

The Reality of the 'Thankless' Caregiver

Let’s perform some reality surgery: Your parent is probably never going to have a 'The Notebook' moment where they look you in the eyes, thank you for your sacrifice, and apologize for being a nightmare. If you are waiting for that to happen before you allow yourself to feel peace, you’re essentially holding your breath until you pass out. The truth is that caring for difficult elderly parents often involves managing caregiver anger and resentment that feels like a hot coal in your chest.

He didn't 'forget' that you have a life; he prioritized his own immediate comfort because he is now the center of his own diminishing universe. When you are dealing with personality changes in aging parents, the old versions of them are gone. Stop trying to negotiate with a ghost. You need to implement emotional detachment techniques for caregivers immediately. This means doing the work of caring—the baths, the bills, the doctors—while mentally checking out of the emotional drama. If they scream about the soup being cold, the fact is the soup is 180 degrees and they are just angry at being old. Don't own their anger. It’s a heavy coat; you don’t have to put it on just because they’re holding it out for you.

Scripts for Diffusing Heated Moments

To move beyond feeling into understanding is the first step, but the second step is purely tactical. When you are in the room with them, you need a social strategy that preserves your energy. Effective caregiver boundary setting isn't about changing their behavior—it’s about changing your response. When they engage in irrational circular arguments, do not explain. Explaining is a low-status move that invites more debate.

Here is the move: Use 'The Broken Record' technique combined with a hard exit. If they are demanding something impossible, say: 'I understand you're frustrated, but I cannot do that right now. I’m going to go into the other room for ten minutes so we can both reset.'

If they attack your character, use this script: 'I’m here to help you with your physical needs, but I’m not available to be spoken to that way. If it continues, I’ll have to leave for the afternoon.' Then, and this is the most important part, you must actually leave. High-EQ strategy requires you to value your own peace more than their temporary compliance. You are the chess player here; they are just reacting to the board.

FAQ

1. How do I handle the guilt of wanting to put my parent in a facility?

Guilt is often a sign that you are holding yourself to an impossible standard. Transitioning to professional care isn't abandonment; it is a strategic decision to ensure they have 24/7 medical supervision that a single person cannot safely provide.

2. What are the signs of caregiver burnout when dealing with difficult parents?

Key indicators include chronic physical exhaustion, a sense of hopelessness, increasing resentment toward the parent, and neglecting your own health or social relationships.

3. Can I set boundaries with a parent who has dementia?

Yes, but the boundaries are for you, not them. You cannot expect them to remember a 'rule,' so your boundary must be an action, such as leaving the room when they become verbally abusive.

References

psychologytoday.com — Caring for an Aging Narcissist

nia.nih.gov — Coping with Difficult Behaviors in Dementia